|

D-Lib Magazine

November/December 2013

Volume 19, Number 11/12

Table of Contents

Descriptive Metadata for Field Books: Methods and Practices of the Field Book Project

Sonoe Nakasone

District of Columbia Public Library System

sonoe.nakasone@dc.gov

Carolyn Sheffield

Smithsonian Institution

sheffieldc@si.edu

doi:10.1045/november2013-nakasone

Printer-friendly Version

Abstract

Field books are primary source materials documenting the events leading up to, and including, the collection of specimens or observation of species for the purposes of natural history research. The mission of the Field Book Project (FBP) is to create one online location for field book content. The FBP uses the collection and item level descriptive standards Natural Collections Description (NCD) and Metadata Object Description Schema (MODS), respectively. Additionally, field book creators are described using Encoded Archival Context (EAC). In this paper we explain the descriptive metadata used by FBP for field books, which share characteristics of museum, archives, and library objects, and explain why these schemas were chosen, how they are used, and the challenges and future goals of FBP.

Keywords: Field Book, MODS, NCD, EAC, Descriptive Cataloging, Metadata

Introduction

Biodiversity research begins with field books, primary source documents which record information about what was observed, discovered, and collected in nature. On account of their integral relationship to specimen collections, field books are often consulted by both new and established researchers for various reasons. Yet it is this close relationship to the specimen collections, along with their nature as primary source documents, which make their categorization as objects ambiguous. Are field books museum objects that should physically reside close to specimen collections and be described and made available in a similar way? Are these archival materials that should be stored and preserved in archives and described in finding aids? Or should these book-like resources be considered library objects to be cataloged as individual volumes in an online catalog? Perhaps aspects of all of the above are valid.

In this paper, we describe the descriptive metadata approach implemented by the Field Book Project (FBP) to address the overlap of field books as museum, archives, and library objects. This paper focuses on metadata for the original, physical objects, and not their digital surrogates. In Overview of Metadata and Content Standards we introduce the descriptive metadata standards and concepts of "collection" and "item" as applied on FBP. In Metadata Approach and Practices we present how these metadata and content standards are used to bridge library and archival practices of description. Following the explanation of the metadata, we present examples of records. Finally we conclude with challenges and future plans for the project.

Project Overview

The FBP is a joint initiative of the Department of Botany, National Museum of Natural History (NMNH), and the Smithsonian Institution Archives (SIA). One inspiration for the project was Co-Investigator Rusty Russell's search for field notes from the United States Exploring Expedition (1838-1842) that led to holdings in over a dozen institutions. The experience was frustrating: little to no information was available and therefore there was no way to establish a clear idea of the content of the field notes without travelling to each institution. Co-Investigator Anne Van Camp, Director of SIA, had also identified the need for better description of field books. As the Smithsonian's institutional archives, SIA houses thousands of field books but, as is the standard in archives, descriptions of individual items within collections were minimal and field books are often found within larger collections comprised of other personal papers or institutional records. Recognizing their mutual goal of improving access to field books, Russell and Van Camp envisioned a Field Book Registry (FBR)1 to serve as a single location for primary source field research materials all over the country—an OCLC for field notes.

In addition to OCLC's WorldCat, projects like Biodiversity Heritage Library (BHL) and Digital Public Library of America (DPLA) provide collaborative models for the FBR. Today, OCLC enables and assists libraries across the country to catalog their published (and sometimes manuscript) materials and share records of their holdings with each other through the union catalog known as WorldCat. Similarly, BHL unites published biodiversity materials that may be incomplete at any one institution into one online repository of digitized content with user-friendly metadata. DPLA is a large scale initiative for developing tools and services for providing broad public access to digital collections throughout the country.

Together, NMNH and SIA applied for and received funding from the Council of Library and Information Resources (CLIR) to uncover the "hidden collections" of field books at the Smithsonian. The Field Book Project is currently in the first of two phases. Phase one focuses on creating and making publicly available catalog records for the Smithsonian field books. During phase two, these records will be migrated to a robust, XML-driven FBR which will be opened to other institutions to add catalog records for field books in their repositories. Throughout this paper, we will refer to any specific data elements by the proper XML tag from the respective schemas that will be used in the final Registry.

Field books at the Smithsonian Institution are maintained by multiple departments or units: natural history departments, Smithsonian Institution Libraries (SIL), and SIA. Some departments, like the Department of Botany, created inventory lists with basic information to help staff members and patrons find the field books they needed. In other natural history departments, SIA created basic finding aids in the 1970s and 1980s and did some light processing, but the collections remained in the custody of their departments. These earlier finding aids have been very helpful as a foundation for description, but are outdated in many cases.

The CLIR grant provided generous funding for the cataloging efforts for Smithsonian field books. Digitization and conservation are also critical to the longevity of these materials and the success of this project. Funding from the National Park Service Save America's Treasures program supported the FBP in providing conservation treatment that stabilizes field books for digitization. Funding from the Smithsonian Women's Committee enabled additional conservation and digitization of the field books. Digitization was seen as an extremely important part of the project from the beginning and, as such, the FBR is being developed to support page level navigation of digitally imaged field books. This paper will focus on our cataloging methodology. While the bulk of our records are now available online through the Smithsonian's Collections Search Center, the details of end user delivery including the future XML Registry features, as well as the details of the conservation efforts and digitization goals, will be discussed later elsewhere.

Field Books as Unique Materials

Field books or field notes (used interchangeably from here on) are unique because of the original information they provide, their integral relationship to specimens, and the variety of formats and material types they encompass.

Field notes are documents created during field research relating to and usually resulting in the collection and deposition of natural history specimens. This definition is meant to be inclusive. Michael Canfield notes, "Even considering the materials available, a serious naturalist-scientist is still left to ponder how field notes can be recorded efficiently and effectively. The answer [...] is specific to the nature of the author and the need addressed."2 Field notes, therefore, vary greatly and depend upon the collector, time period, subject, and other factors. Despite the variety in field notes, Canfield offers the following "loose categories" of field notes: diaries, journals, data, and catalogs. There is often significant overlap between these categories. Diaries and journals may both record daily activities, but Canfield suggests diaries will include the mundane, whereas journals will contain basic observations related to field work. Canfield continues: "Data entries encompass substantial behavioral observations, factual records, and experimental results; and catalogs record things collected and observed." Adding further to their variety, field notes as physical objects can be paper documents (bound or loose notes), film, tape, photographs, or electronic records.

Other material types and genres should also be considered field notes when created for the purpose of researching species in the field and when they supplement list or journal entries. Such materials include sketches, maps, photographs, correspondence, motion pictures, sound recordings, and any number of other formats we have yet to encounter. Often these materials are bound with, inserted in, or accompany a particular set of textual field notes. At other times, these materials are separate entities, for example, a photo album.

Information Needs

To get a sense of the information sought from field books, we conducted a brief qualitative survey. While we received only 39 responses, the results were useful in understanding the value of these materials. Reference questions received during the first two years of the project were also reviewed for further insight into recurring information needs.

In response to the open-ended question "What kind of information are you seeking when you consult field books," the two highest numbers of respondents cited locality information (67%) and specimen information (55%). For the same question, the next highest number of respondents cited environmental and habitat location (41%), followed by respondents who cited dates and historical narrative / personal observation information (15% each). A review of reference questions received during the course of the project revealed similar results regarding locality information: 67% sought field notes from specific localities.

Overview of Metadata and Content Standard

Field books are held in the stewardship of museums, archives, and libraries, and therefore benefit from a flexible yet consistent method that combines descriptive practices from all three fields. The FBP draws from metadata and encoding schemas and content standards from all three disciplines to create a hybrid descriptive framework that bridges collection and item level description. We will introduce the descriptive practices which we draw from and then present how we define collections and items in the context of field books.

Collection and Item Level Metadata

Collection level metadata is a hallmark of archival description. Archival finding aids describe materials as collections, rarely becoming more granular than brief folder level descriptions. In archival description, providing the context in which materials were created is as important as describing the materials themselves. Four of the eight basic principles outlined in Describing Archives: A Content Standard (DACS)—records possess unique characteristics, respect des fonds (the principle of maintaining original order, structure, and provenance), description reflects arrangement, and describing creators of records3—reflect the importance of contextual information in finding aids. Unlike published works, which are self-justifying and stand alone objects, archival documents are like pieces of a puzzle; although they are useful on their own, they rely upon other documents within the collection to tell a full story. It is for this reason—to provide context and preserve relationships between items within field book collections—that we use collection level descriptions.

Although Chapter 4 of Anglo-American Cataloging Rules, 2nd Edition (AACR2) has instructions on cataloging manuscripts, library metadata has traditionally focused on describing published materials, and as such, library standards have been less concerned with providing contextual, collection level metadata. Libraries have, however, long been innovators for item level metadata, which has traditionally emphasized access points like authors or creators, subjects (e.g. topics, locations, names), and titles. Recall from the Information Needs section above that those granular access points of geographic and topical coverage are incredibly important for addressing the bulk of known research needs for primary source field notes. These allow researchers to more easily pinpoint desired volumes. Additionally, item level access is crucial when we consider the goal of providing online access to digitally imaged field books. A prolific scientist may create over one hundred field books over the course of her career, spanning collecting events across the globe. Distinguishing one volume from the next based on content, therefore, becomes important for meeting information needs. Furthermore, libraries are precedent setters for controlled vocabulary within access points. For these reasons, we also catalog at the item level, primarily following library descriptive practices.

An explanation of what we consider a "collection" and "item" follows.

A "collection" is defined as any group of field books with a unifying relationship4. Field book collections can be assembled in many ways; Smithsonian collections, however, are usually grouped by collector or expedition. For example, a collection grouped by the collector Alexander Wetmore would consist of field books created or owned by Wetmore. Alternatively, a collection grouped by the expedition United States Exploring Expedition might consist of field books created by various individuals that participated in that expedition. Less frequently, collections are assembled by the organizations as a creator. However they are grouped, collections are determined based on the way the field books were physically organized, with respect to the provenance and order in which they were received and maintained, prior to our involvement, in accordance with archival practice5.

An "item" is an individual field book, whether bound or unbound. If bound, a field book more resembles a library object, usually a discrete cover to cover unit. If unbound, a field book might be housed in a folder and document box, as in an archive. Although an unbound field book is still considered one "item," storage constraints may require that it is physically separated into multiple folders.

Describing field books at both the collection level (an archives convention) and item level (a library convention) allows us to capture the full range of contextual and descriptive information. Additionally, cataloging at both levels enables others interested in following this model to start at the collection level if they do not have the resources for item level cataloging.

Encoding Schemas and Content Standards for the Field Book Project

For collection level and item level records, we work with two metadata schemas: Natural Collections Description (NCD)6 and Metadata Object Description Schema (MODS), respectively. In following the archival principle of describing creators, we also use Encoded Archival Context (EAC) to create authority records for individual collectors, organizations, and expeditions. All three schemas are available as XML and will facilitate crosswalking with other commonly adopted schemas such as MARC, Encoded Archival Description (EAD), and Dublin Core (DC). Details on how records in these schemas relate to one another are provided in the Metadata Approach and Practices section. Additionally, two content standards were chosen to guide the selection and formatting of information entered into our bibliographic records: AACR2 and DACS.

NCD was developed by Biodiversity Information Standards (formerly Taxonomic Databases Working Group and still known as TDWG) to serve the natural history museum and research community. NCD describes collections of specimens as well as archival collections about specimens. A detailed explanation of the elements are available on the TDWG website. As Elings and Waibel note, the uniqueness of museum objects once led the museum community to develop local systems for description.7 Like libraries and archives, museums in this age seek standardization across institutions, and there is greater emphasis now in museums on the importance of user centered descriptions. One advantage of NCD over the archival standard EAD is it contains elements that museums, botanical gardens, and other natural history research facilities typically capture when recording information about specimens, for example, Kingdom, Taxonomic Name, Common Name, Living Time Periods (geological) and Expeditions. These fields contain important information that also responds to the research needs pertaining to field books. Furthermore, with the integral relationship between specimens and field notes museum descriptive practices are well-suited for providing some consistency and parity with descriptions for specimens.

The Field Book Registry uses a subset of elements from NCD version 0.7. The decision to use NCD version 0.7 was based on its Dublin Core-based simplicity, its availability in XSD and its ability to easily map to later versions of NCD. The current version of NCD (0.9, awaiting ratification) incorporates RDF8, in an effort to move towards semantic web technology, although at the time of publication the authors are unaware of any current efforts to finalize the implementation of NCD in RDF.

The Field Book Registry uses MODS version 3.4, developed by the Library of Congress, to create item level metadata. MODS was chosen over other possible XML schemas like Dublin Core (DC) or MARC XML because of its balance between simplicity and granularity. MODS requires only a few elements, unlike MARC XML, yet is capable of more robust descriptions than Dublin Core. Record creators are therefore able to choose the appropriate level of detail. Furthermore, MODS retains enough of the essential features of MARC to make it a more appropriate choice for document-like objects over schemas like Cataloging Cultural Objects (CCO) for museum realia. Finally, Library of Congress maintains a cross-walk between MODS and MARC for easy mapping and to promote interoperability between the two standards.

EAC was developed by the Society of American Archivists and Staatsbibilothek zu Berlin to create archival authority records.9 The advantage of EAC over MARC XML and Metadata Authority Description Schema (MADS) is the emphasis on contextual information and the ability to outline relationships between entities. Currently, Social Networks and Archival Context (SNAC), directed by Daniel Pitti, seeks to create an integrated system using EAC to link descriptions of persons to each other and to archival resources from various institutions10. These linkages will make it possible to both ensure consistent name entry and to enable institutions to contribute more details about a person's, organization's or expedition's history that is specifically tied to the collections in their custody.

Content standards for cataloging in the Field Book Registry are based on AACR2, particularly chapters 1 (general rules), 2 (books), and 4 (manuscripts)11. The authors acknowledge AACR2's replacement with Resource Description and Access (RDA)12 and have avoided implementing practices that heavily contradict the new standard when possible. These standards are evaluated against the needs of the project and the researchers the project serves. Where AACR2 provides insufficient guidance for cataloging field books, we turn to DACS. When further guidance is necessary, we consult natural history researchers and curators to determine how best to serve their needs, and consult our library and archives colleagues.

Metadata Approach and Practices

The structure of the Field Book Registry combines collection (NCD), item (MODS), and authority (EAC) records into one database. Explicit and implicit connections between each of the records depict their relationships with one another and unite records with related content. Explicit connections are facilitated by references embedded within the metadata, linking one record to another. Implicit connections are facilitated by the use of standardized vocabulary enabling items from separate collections—albeit with common threads—to be retrieved together through searching or faceted browsing. Below, we outline the main explicit and implicit connecting points found in FBR records. We also discuss examples of FBP records from screenshots of the local database.

Explicit connections: Item (MODS) to Collection (NCD) and Item to Authority (EAC)

Explicit Connections between Items (MODS) and Collection (NCD)

Collections are, in essence, the hierarchical parent of items, and this relationship is captured through explicit references in the MODS records. The name and ID of the collection to which an item belongs is included within each item record. For this, we use the MODS element <relatedItem> and modify it with the attribute and value combination @type="host," creating <relatedItem type="host">13. The "host" value indicates that the <relatedItem> is the parent collection as opposed to a relationship of a different nature to other materials. Additionally, an ID attribute is added to store information about the collection ID within the MODS record, making the connection immediate and less ambiguous. Dropdown menus are populated with the collection name and ID from the collection record and facilitate adding this data to the item record.

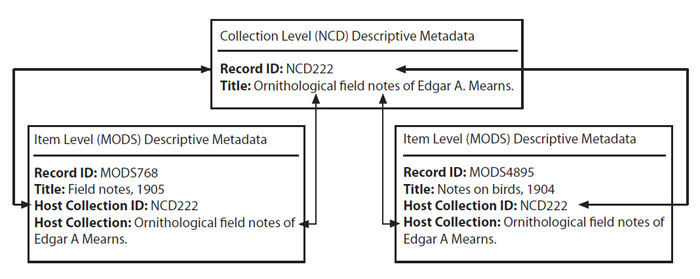

The arrows in Figure 1 below pointing from the "Host Collection ID" to the collection record ID and the arrows pointing from the "Host Collection" title in the item record to the Title in the collection record illustrate this direct and explicit connection. Although it is possible to include links to items within a collection record, the system will instead enable connections by executing a script to retrieve a list of items.

Figure 1: Explicit Connections between Collection (NCD) and Item (MODS) Records

Explicit Connections between Authority (EAC) and Collection (NCD); Between Authority (EAC) and Items (MODS)

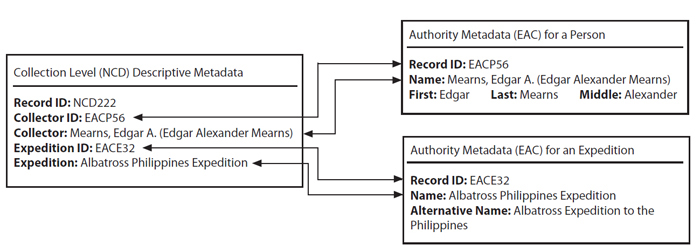

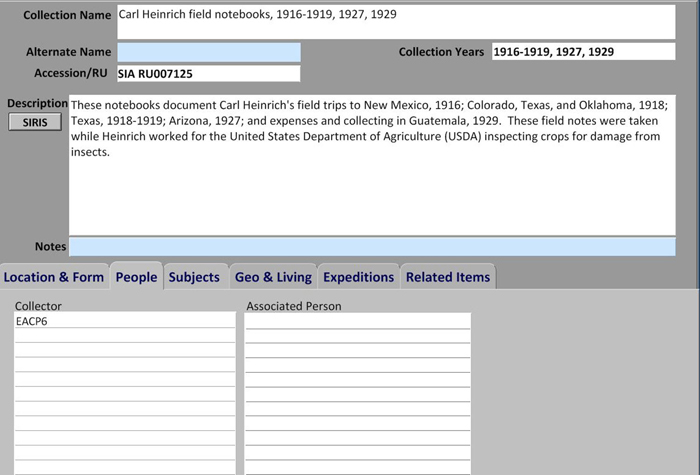

Both collection and item records contain fields that directly refer to entities described in authority records. NCD records contain the elements <Collector>, <AssociatedPerson>, and <Expedition>, all of which may refer to persons, organizations, or expeditions represented by EAC records (see Figure 2).

Figure 2: Explicit Connections between Collection (NCD) and Authority (EAC) Records

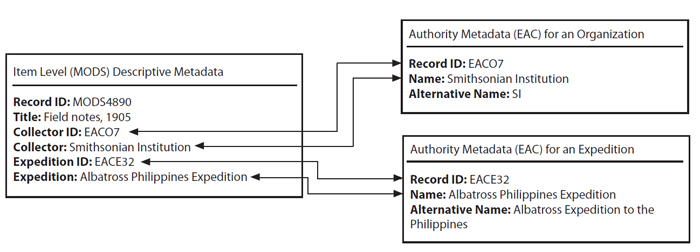

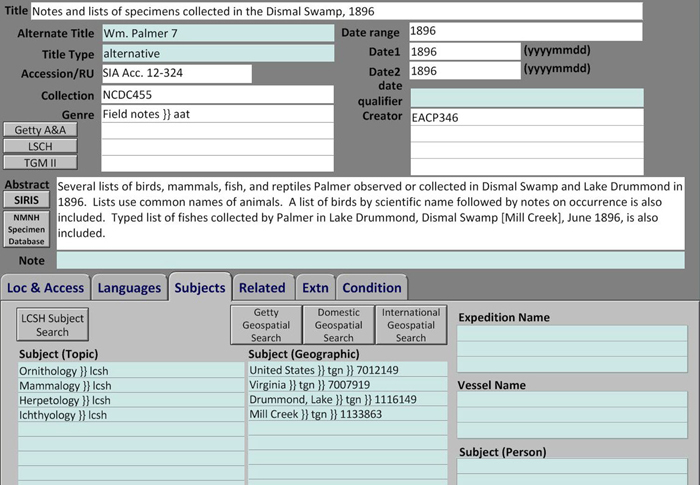

Similarly, MODS records contain the element <name>, for which person, corporate, and conference names are included (see Figure 3).

Figure 3: Explicit Connections between Item (MODS) and Authority (EAC) Records

Type attributes distinguish between the types of entities being referenced. In MODS, for example, an explicit reference to an EAC person record is included in the tag <name type="personal name"> whereas a reference to an EAC organization record is expressed as <name type="corporate name"> and expeditions as <name type="conference">. In MODS, the role of the entity (e.g., creator, contributor) is also expressed through attributes. Distinguishing between entity types and roles makes it possible to map neatly to the MARC 100, 110, and 111 fields for creators and 700, 710, and 711 for contributors.

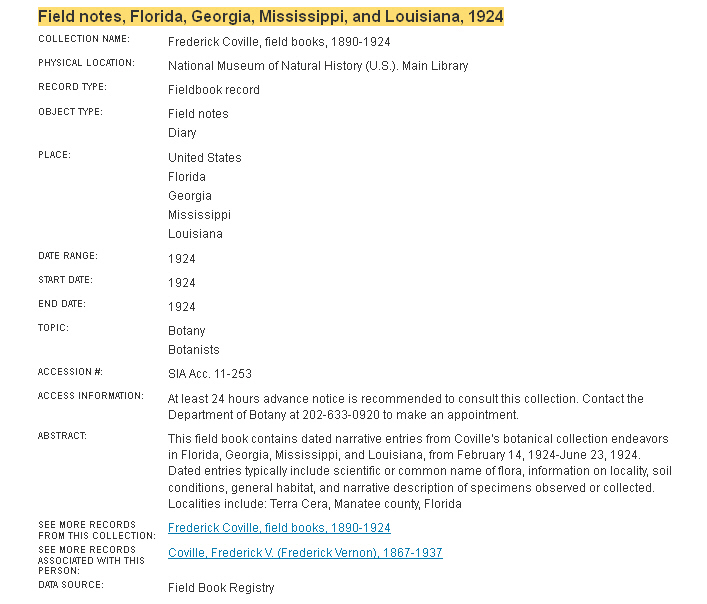

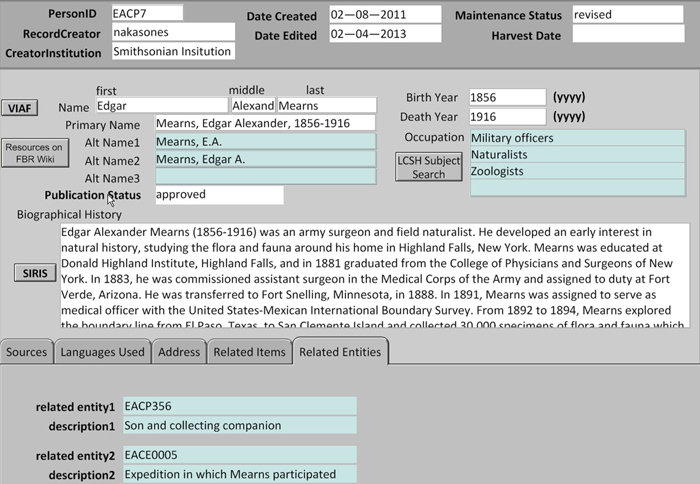

The names of persons, organizations, and expeditions are taken from the Virtual International Authority File (VIAF), the Smithsonian Institution Research Information System (SIRIS), or are formed according to the Name Authority Cooperative (NACO) rules. In EAC records, these name headings are recorded in the <name> element. The EAC <name> element corresponds to the MODS <name> element, labeled "Collector" in Figure 3 above. To make the reference to EAC records less ambiguous, the EAC record ID is also included in the MODS record. Once the EAC record is created, catalogers enter EAC record IDs for the entity described into the MODS record using an automatically populated drop-down menu. For display purposes, a script uses the EAC record ID, stored as a reference in the MODS XML, to call the EAC record and display the authorized form of name rather than EAC record ID to the end user. Currently, in the Smithsonian's Collection Search Center, the collector name is displayed with the label "See more records associated with this person" and hyperlinked to other records that contained the same identifier or name string (see Figure 4).

Figure 4: Example of hyperlinked authorized name headings displayed in place of EAC identifiers, from Smithsonian's Collection Search Center

Currently, the explicit links between MODS or NCD records to EAC is one-way: MODS and NCD records include links to entities described by EAC records but not the other way around. Although EAC contains the necessary elements and attributes to link to item and collection records, we are not devoting resources to manually input these links.

EAC records are also explicitly linked to other EAC records. These references are entered into the record manually so only major relationships are recorded at this phase in this project. Within the person EAC records, up to three related persons or organizations are included. Within Expedition records, up to 10 person participants and 10 organization participants are included. As with the other explicit connections between records, the connections are facilitated by using record IDs.

Implicit Connections: Items (MODS) to Items, Collections (NCD) to Collections

In addition to the hard and direct references from one record to another, implicit connections between collection, item, and authority records are possible through the use of consistent and controlled vocabulary in key access points.

Consider that a researcher might want to know what was collected in a particular location (recorded as a geographic subject in MODS). The name for a particular locality may vary within the field notes of various collectors because of border and boundary changes (e.g. British East Africa vs. Kenya), names of places in various languages (e.g. Bering Island vs. Ostrov Beringa), inconsistent spellings or transcriptions of place names (e.g. Chengtu vs. Chengdu), and other factors. Consistently applying standardized vocabulary for geographic names is crucial to retrieving items referring to the same locality despite the use of different names. Currently, the preferred source for geographic names for this project is the Thesaurus of Geographic Names (TGN) maintained by the Getty Institute. When TGN is insufficient, we turn to GeoNet Names Server (GNS), developed by the National Geospatial-Intelligence Agency and the Geographic Names Information System (GNIS) developed by the United States Geological Survey, and then finally LCSH. Similarly, collection records are implicitly related to other collections through the use of controlled vocabulary. Like MODS, NCD includes an element for recording geographic names. NCD also contains fields for Kingdom Coverage and Taxon Coverage for which controlled vocabulary is used.

Cataloging Examples

The local database cataloging interface is tailored to cataloger needs. Development of the final FBR is currently focused on these cataloger functions and not the public interface. In this section, we share screenshots of the collection, item, and authority records in the local database and discuss these examples. Rather than discuss the entire list of elements for each record, we will focus on the descriptive metadata including important controlled vocabulary access points and free text fields in each example. For the collection record, we focus on archival and natural history access points and the free text "Description" and "Notes" fields. For the item record, we focus on the importance of both common access points and the note field. For the authority record, we discuss the "Name" access point and the free text "Biographical History" field.

Collection records include both traditional bibliographic and natural history controlled vocabulary access points. Records also contain free text fields that do not require the use of controlled vocabulary. Traditional bibliographic access points that use controlled vocabulary include names, geographic subjects and natural history terms. For names of collectors or associated persons (Figure 5) catalogers use headings from VIAF and other authorities. Catalogers also enter the record ID of the collector's EAC record, although only the collector's authorized name heading is displayed to the end user. Geographic locations ("Geo & Living" tab in Figure 5) are recorded using standardized vocabulary, generally from TGN. Additionally, controlled vocabulary access points from the natural history world are included. Recall from earlier that 55% of survey respondents cited information on specimens as a reason for consulting field books. Therefore, including Kingdom and Taxonomic Coverage (family level or higher) in the collection record—information often recorded in specimen databases—satisfies a researcher need. Data values for "Kingdom" are predetermined within the NCD schema. For Taxonomic Coverage, we use terms from uBio (www.ubio.org). Expedition names are either from VIAF, or formed using NACO rules. Although the use of standardized terms in Common Name Coverage is encouraged, this field does not necessarily use standardized vocabulary to accommodate the plethora of common names.

Figure 5: Collection record (NCD): Carl Heinrich notebooks, 1916-1919, 1927, 1929

Equally important to discovery and assessment of relevant field book collections is the free text "Description" field. Similar to the "Scope and Contents" element outlined in DACS, this field discusses the activities that generated the field notes, describes the formats and genres included, provides dates, geographic locations, lists topics and themes, and contains any other information useful for assessing the collection.14 Additionally, a note field is provided for general notes (similar to MARC 500) or to be used as any of the note types found in DACS.

The unique content and format of field books prompted us to create item records that rely heavily on both bibliographic controlled vocabulary access points as well as free text note fields. Access points within item records support browsing based on standardized vocabulary. Visible in Figure 6 are the item level access points, which include five subject fields: genre subjects <genre>; topics <subject/topic>; geography <subject/geographic>; organizations <subject/name type="corporate">; and Persons <subject/name type="personal">.

Figure 6: Item record (MODS): Notes and lists of specimens collected in Dismal Swamp, 1896

Topical subjects are taken from LCSH, name subjects from VIAF and SIRIS. Geographic subjects use TGN, GNS, and GNIS. Subject fields also contain additional data: the source of the controlled term and, for geographic names, the numeric ID for the controlled term. As manuscripts, field books contain unpredictable physical contents and information formats. While this field is not considered a necessary access point for published materials, <abstract> is a required field for this project. Here we record non-standardized vocabulary such as historic or local geographic names, summarize often diverse, perplexing, and voluminous content, and manage researcher expectations of field book content. The item-level <abstract> differs from the collection level <Description> (Figure 5) because <Description> contextualizes relationships between items within a collection. By contrast, the <abstract> summarizes the content within an individual field book, although occasionally references to related items are included. A separate "note" field is used either as a general note, as in MARC 500, or as any of the MODS recommended note types.15

Authority records are created for persons, organizations, and expeditions. These authority records serve a few purposes: 1) provide authoritative form and variant forms of names; 2) provide the history of the entity; 3) reference related entities; and 4) reference related collections. FBP authority records currently focus on 1) and 2), and often include 3).

Figure 7: Authority record (EAC) for the Entomologist Carl Heinrich

Like the FBP bibliographic records, authority records contain controlled vocabulary access points and free text descriptive fields. The most important controlled access point of the authority record is the "Primary Name" (<name>) field because it is the standardized name by which the entity is most commonly known. For person records (Figure 7), names in the "Primary Name" field are taken from VIAF, SIRIS, or are formed following Name Authority Cooperative (NACO) standards. Authority records also contain the element "Biographical or Historical Note" (<biogHist>) (also shown in Figure 7), which is the most important free text field. <biogHist> provides a brief narrative of the key points of the person's life and career, or in the case of expeditions and organizations, the formation, major events, and history of those entities. This narrative may also include an explanation of relationships between EAC records, including institutional affiliations and participation in expeditions.

See more examples of Field Book Project records here (or visit http://collections.si.edu and enter "unit_code:FBR" into the search term box).

Challenges and Future Direction

Although there are many challenges we face when cataloging field books one of the most difficult is granularity. Our goal is to create metadata that responds to known information needs while balancing the time needed to find and convey that information. We also strive to make our workflows as repeatable as possible for both large and small organizations. The challenge of establishing consistent practices for institutions of varying resources is compounded by the sheer variety of materials which can be considered field books.

Field notes range from a few pages to hundreds. For field books containing larger amounts of information, choosing a cut off point for description is difficult. When cataloging field books, we look at some traditional bibliographic access points—creators and subjects (topical, geographic)—along with dates and other subject specific access points such as taxonomic coverage, collection numbers, vessels, and expeditions.

Among the access points listed above, geographic information is one of the most challenging. As noted earlier, a majority of the reference questions received relate to geographic information. One field book could easily contain 50 terrestrial or marine localities. The challenge: efficiently recording this potentially complicated geographic information. We employ a number of approaches in capturing geographic data including sampling and grouping. Sampling may be methodical, random, or used to illustrate a general route. Grouping involves describing at higher levels in the geographic hierarchy that include several localities. In addition to the number of geographic locations, we face the problem of ambiguous geographic names. For example, popular names like "Bear Creek" occur in multiple counties within multiple states. Depending on the detail provided in the field notes, it can be difficult to determine which of three neighboring states the collector travelled through is being referenced.

In the future, we anticipate that crowdsourced transcriptions and geo-tagging will help to overcome many of these challenges of granularity. Crowdsourced transcriptions can make the rich content in field books not only viewable, but full-text searchable, effectively unlocking the data. To this end, 10 digitally imaged field books have been included in the Smithsonian's beta Transcription Center and the public has already begun contributing transcriptions. Several other projects are already crowdsourcing to improve access to archival documents. One such project is the Zooniverse OldWeather project. OldWeather relies on "citizen scientists" or well-informed enthusiasts in the public to transcribe weather observations from WWI Royal Navy ships' logs. Volunteer transcribers select sections of the document to transcribe into an easy to use interface.16 OldWeather's Royal Navy logs project boasted 97% accuracy for their crowdsourced transcriptions.17 The United States Geological Survey's North American Bird Phenology Program (BPP) has also started an easy to use crowd-sourcing transcription project that, like OldWeather, validates the accuracy of crowdsourced transcriptions by evaluating agreement across multiple versions.18 Ben Brumsfield's FromThePage uses a successful "open-ended community revision" approach for crowdsourced transcriptions, a model in which there is "no final version."19 A document is transcribed once, and members from the community are allowed to edit the transcription indefinitely. A project by So You Think You Can Digitize writers Andrea Thomer and Rob Guralnick crowdsources annotations for the field notes of Junius Henderson, which are already scanned and transcribed. Wiki style mark-up templates enhance the transcribed texts, making the content more discoverable. Volunteers use these templates to mark up taxa, locations, and dates, which eventually become occurrence records (Bloom, Thomer & Guralnick, 2012)20 . The FBP has not yet chosen which model or models it will use to encourage wide participation with effective outcomes, but the examples above serve as excellent examples of successful crowdsourcing initiatives that may be followed.

The approach described here is not prescriptive, but it does provide a framework for other institutions interested in cataloging primary source field research materials. The multiple levels of description accommodate institutions of varying resources. This model provides institutions with large staff support with guidance for the creation of item level bibliographic description, contextual collection level metadata, and authority metadata for entities described in field books. Institutions with fewer resources may choose to catalog at the collection level until resources become available for a more granular level of description. Furthermore, these institutions can take advantage of the EAC authority records created by other institutions to use in their own local databases. Remember that one of the impetuses for this project was a search for the Wilkes Expedition field books held at approximately a dozen or so institutions and the lack of information on what was to be found at each repository. Once the Registry opens for external content and more institutions add data about their field books into the FBR, and link those records to the EAC expedition record, the hunt for Wilkes Expedition field books, and many other searches like it, will be faster and easier for both researchers and the reference staff serving them.

Although we have already made a great deal of progress towards these goals, we recognize that there is still much to be done. Approximately ninety percent of known SI field book collections are cataloged but the continuing process of developing the XML-driven version of the Registry means that some of our envisioned features for accessing the materials are still on the horizon. Additional funding for digitizing and preserving field books will be needed to make these field notes available online and increase the life of the original items. Even if all the field books in the country are made available online, then what? How will the relationships between the field notes, the specimens they describe, and grey and published literature about the specimens and the events surrounding their collection be connected in a systematic environment? How will creators of field notes and collectors of specimens be described and connected to their peers, their expeditions, their institutions, their collections? Finally, how will we endeavor to create these connections in a responsible way that is consistent with the growing trend of the semantic web that seeks to illuminate the connections between all related content on the web? Many of these questions are already being investigated by colleagues in libraries, archives and museums throughout the world, and we look forward to working with them in the ongoing conversation on how to increase access to and unity among important content.

Notes

1 Throughout the paper, we will use FBP to refer to the Project and FBR to refer to the Registry being developed on the Project.

2 Michael Canfield, Field notes from science and nature (Boston, MA: Harvard University Press, 2011), 11.

3 Society of American Archivists, Describing archives: A content standard, (Chicago: Society of American Archivists, 2004), xi-xv.

4 Ibid, 203.

5 We retain the organization of collections already accessioned by SIA. We use descriptive information in finding aids, when available, as a spring board for our own records and to maintain consistency. For collections maintained by museum departments, generally each collector is given her own collection because that is how the museum organizes it. If the museum chose another way to organize a collection, for example, kept all the field books inherited by another museum together as one group, we would organize the collection in the same way.

6 Biodiversity Information Standards (TDWG), "Welcome to the NCD Web".

7 Mary W. Elings and Günter Waibel, Metadata for all: descriptive standards and metadata sharing across libraries, archives, and museums, (First Monday, 2007), vol. 12, no. 3.

8 Tom Heath, "Linked data". RDF is a language for describing web resources. It is a common framework that allows information to move between applications by using Unique Resource Identifiers (URIs) to identify objects. RDF is one of a few technologies used to support Linked Data, which enables data on the Web to be linked. One purpose of Linked Data is to transform the Web from a hodgepodge of unrelated data into a Semantic Web in which related data is connected, more easily facilitating collaborations and exposing trends and commonalities.

9 Society of American Archivists, EAC-CPF Schema.

10 Social Networks and Archival Context Project. SNAC: Social Networks and Archival Context Project.

11 Anglo-American Cataloguing Rules (2nd ed.), (Chicago: American Library Association, 2005).

12 RDA is being developed as a replacement to AACR2. RDA will include guidelines on cataloging digital resources, support clustering of bibliographic records, and emphasize the Functional Requirements of Bibliographic Records (FRBR) model.

13 Although we are currently working in the OTS FileMaker Pro relational database system, we have structured our database to map directly to these XML schemas in the Phase Two Field Book Registry. For this reason, when discussing specific data elements we refer to them by their proper xml tag from the respective xml schemas.

14 Society of American Archivists, Describing archives: A content standard, (Chicago: Society of American Archivists, 2004), 35-36.

15 Library of Congress, MODS <note> Types.

16 "OldWeather: Our Weather's Past, the Climate's Future".

17 Better than the Defence. Old Weather Blog.

18 Jessica Zelt, Presentation to Smithsonian Institution employees, February 13, 2012.

19 Ben Brumfield, "Quality control for crowdsourced transcription", Collaborative Manuscript Transcription Blog.

20 Andrea Thomer and Robert Guralnick, So You Think You Can Digitize. The Henderson field notes inspired Thomer and Guralnick to create WikiProject Field Notes, a wiki for institutions interested having their field books annotated in Wikisource. David Bloom, Laura Russell, and Guarav Vaidya have also made significant contributions to the project.

About the Authors

|

Sonoe Nakasone is the former Cataloging Coordinator on the Field Book Project. Ms. Nakasone has developed her focus on cataloging and metadata through her work with various formats in diverse library and archival settings. In addition to her MLIS from Pratt Institute (New York, NY), she also holds certificates in archives and museum librarianship. She is currently a cataloger for the District of Columbia Public Library system.

|

|

Carolyn Sheffield Carolyn Sheffield is former Project Manager for the Field Book Project at the Smithsonian Institution. In this position, she led the metadata design for the Field Book Registry and digital outreach efforts for the Smithsonian's field book collections. Her interests include user needs for information access, open access digital libraries, and new media. She holds a Master of Library Science degree from the University of Maryland, College Park with a concentration in archives and records administration. She is currently Program Manager for the Biodiversity Heritage Library.

|

|