|

|

|

| P R I N T E R - F R I E N D L Y F O R M A T | Return to Article |

D-Lib Magazine

July/August 2015

Volume 21, Number 7/8

"Bottled or Tap?" A Map for Integrating International Image Interoperability Framework (IIIF) into Shared Shelf and Artstor

William Ying and James Shulman

Artstor

{william.ying, james.shulman}@artstor.org

DOI: 10.1045/july2015-ying

Abstract

Frustrated by the way in which media collections were growing up within individual collecting institutions that were in turn making individual technology decisions about data stores and presentation applications, a community of library technologists set out to design a set of protocols for calling, ordering, and using image files in standardized ways resulting in The International Image Interoperability Framework (IIIF). In this article, we map out how the non-profit organization Artstor (via its Shared Shelf asset management service and its Digital Library) are putting this emerging interoperability standard into practice.

1 Shared Shelf and Artstor Background

Fewer thought experiments are more surreal than mentally tracing how 12 ounces of water from the French Alps or the mountains of Fiji come to the corner grocer where you live. Plastic bottles are created, branded, and shipped to Fiji. Water is bottled and shipped around the world. Tariffs are charged and water is tested. Trucks carry water around the country. All in the name of providing a drink of water. The costs of this discontinuous infrastructure are borne both by the individual buyer and by the society that bears the collective costs generated along the way in terms of environmental impact. Of course, some bottlers and shippers and truckers probably net profit along the way as well. But is it an optimal flow, or just the one that we have? All of us who play a role in the creation of academic cyber-infrastructure should try to learn from the bottled water status quo. In particular, are there possibilities where digital content can be allowed to flow continuously (like water in the ground or in pipes) rather than be delivered in distinct, isolated, and unconnected packages (analogous to 12 ounces of water being separated from its source and transported in separate bottles)? In this article, we map out how an emerging interoperability standard is being put into practice by a series of collaborating repositories and user-facing work environments in which Shared Shelf and Artstor play a connecting role.

Artstor, a non-profit organization originally created in 2001 by The Andrew W. Mellon Foundation, provides a mix of fee-based and free services to the educational community. Known best for its large and growing Artstor Digital Library (which currently provides over 1.9 million high resolution images from archives such as the Museum of Modern Art, Magnum Photos, the Bodleian Library, and over 200 other museums and archives), Artstor also provides free images for use in scholarly publications from over 15 museums through its Images For Academic Publishing program.

Our cloud-based cataloging and asset management service, Shared Shelf, grew out of Artstor's close working relationship with staff at colleges and universities who support faculty members' use of images in their teaching and research. It was clear that faculty members who used Artstor's growing library of images would also need to work with institutional sources of content (primarily their local "slide library" that had grown up around the institution's teaching curriculum) and their own images—photography that they created on site, images culled from journals or books, and images gathered from the web or from friends. Some content that lives in Shared Shelf is shared with local end-users alongside the Artstor Digital Library; other content, such as library special collections can be published into open access sites such as the Digital Public Library of America (DPLA). Other collections can be utilized in an OMEKA site which embeds the content in a collection-specific exhibition website.

Over the past 13 years, our pathway has led us from the challenges of creating a library (from aggregating content, addressing the intellectual property issues, delivering that content, supporting its use) to ever more work in data standards (including a collaboration with the Getty Research Institute and the Avery Library to create (with IMLS funding) a registry of built works) and into cataloging and asset management software. In essence, by setting out to make one shared pool of images, we have moved more and more toward the necessary path of playing various roles in networking many pools of primary source content. Some content has constraints that require it to be used only in access-controlled environments, but other content wants to be free. In 2013, we assisted 6 museums and various Shared Shelf subscribing colleges and universities to channel their content to the DPLA. The Digital Public Library of America (as one example of an aggregator that would benefit from such a service) models its activities on Europeana, which draws content from national digital libraries and other hubs.1 Everything we have done at Artstor has been shaped by the traits of primary source material. We have worked our way through a series of issues that those who work with digital images know all too well:

The challenges associated with digital images include:

- Creating them. Unlike scanning pages of books or journals, many of which are roughly the same sizes and for which the meaning of the work is conveyed in the symbols on the page, images can be all shapes and sizes and they only convey what they convey. In other words, an image can be a picture of a city (in which case thousands or millions of details might be needed to unpack what is pictured) or of a postage stamp. Images can be born digital or scanned from a negative or a print. They can seek to capture a three-dimensional object or a sketch. Photographing a work can be a creative act (think of Julius Shulman's photography of the Case Study Houses) or can seek to slavishly reproduce a painting and aim to provide an invisible frame that grants the viewer unadorned access to the underlying work. Many choices are made by the creator of a digital image—tradeoffs in size and quality, calibration and editing. Museums and libraries have digitized billions of images in recent years, but not without many different decisions and investments having been made.

- Metadata for the images. Unlike scanning images of text that can then be run through Optical Character Recognition and be made searchable, images are only discoverable by the metadata attached to the image file. Someday pattern recognition software will be able to help more with this analysis of the image content itself, but today it isn't there yet. And while descriptive cataloging—one category of metadata—might also serve other purposes beyond discovery (conveying rights information, attribution or other scholarly interpretation), its role in discovery cannot be underestimated. Of course, there are few limits to how an asset could ideally be discovered—the same landscape by John Constable would be sought by an environmental historian using very different terms than it would be by an art historian. But the work of facilitating all of this discovery is both hard and crucial, since, until it is found, the most beautiful digital image in the world isn't evidence for someone's academic work. It's just a silent file on a server.

- Rights associated with the image and the underlying works. How to manage the flow of content while respecting copyright is a challenge for all media in a digital age. For images, these rights issues are complicated in two particular ways: one concerns the two levels of rights that are inherent to digital images and the other concerns the laws of different jurisdictions. Images need to be understood on the basis of the rights pertaining to the work captured in the image (whether intentionally or incidentally) and by the rights of the photographer who created the image of the work, and these rights vary by region or country. Moreover, how images may or may not be used by others (e.g., whether a country has a doctrine of fair use or an educational exclusion to copyright) varies greatly. Apprehension concerning these various intellectual property issues often paralyzes those who are seeking to contribute to the networked flow of images.

- Which image? The creation of digital images is not a magical capture of reality (any more than the printing of an image from film is a mindless reproduction). Decisions, for example, about color correction, or the size of the file to keep or use, have led to many varied paths for collection managers. For many years (when storage was costly), source files were deleted, but for some types of works, keeping each stage of an image in creation is important.

- The management of these digital assets. Digital Asset Management Systems (DAMS) can be costly to implement or build; they may not be easily integrated with other systems; and they require institutions to have answers to many of the questions raised above, few of which are either simple or unchanging. Institutions face daunting challenges in managing (and managing access to) the digital files that they are creating. Shyam Oberoi, formerly of the Metropolitan Museum (now Director of Technology and Digital Media at the Dallas Museum of Art) wisely noted:

...our experience suggests that there are no shortcuts, no easy answers and no way to escape the fact that a DAMS [Digital Asset Management System] is a complex mechanism which, like any enterprise-level application, requires a significant amount of supervision and technical expertise and touches on a range of different information technology and management skill sets, including database administration, web application development, network administration, and storage and backup strategies. (Oberoi, 2008, p.21)2

- Collection owner policies and access controls. Once an institution has its files in order, a whole host of other cultural and business policies need to be set and implemented. Some institutions will want to maintain control over the image (out of a concern for revenue that use of that file might produce or out of a commitment to stewardship of the scholarly record). Various people at an institution—curators, marketing directors, general counsels—may have completely different views on when or how or how widely an image file can be released. And then these various objectives about releasing content have to be carried out, often with hand crafting:

We want to get our collection out there in a variety of ways, but we just don't have the time or resources to craft one submission for this service, another submission for that service, reach agreements with each that respect our requirements. (Jim Maza, Chief Technology Officer for the Walters (conversation with the authors))

In the service of building a library of content that would support the teaching and research needs of faculty and students at a wide range of educational institutions, we have been working through these issues in collaboration with museums, archives, individual scholars, for-profit photo agencies, artists' estates, and many others. We have sought to balance the interests and concerns of the communities involved and to support educational work—providing limited access to very high resolution files without letting them simply fly free; enabling discovery but without being able to re-catalog millions of images; enabling users to work in various presentation softwares while respecting the terms under which the content has been provided. As an intermediary between over 300 builders of digital collections and over 1,600 educational institutions, we have played a role similar to the transportation and logistics infrastructure that supports the transporting of bottled water from Fiji to the corner store.

We believe firmly that the nature of primary source material absolutely requires a networked approach: no one will ever have everything that someone needs to do his or her academic work. But content still will have constraints in how it can flow, and so the network should both be optimized to promote flow and have valves to control what can go where. The latter (the need for some controls out of respect for rights holders' rights or other limiting factors) does not necessitate the proliferation of silos, walls, and locked doors. A great deal of content can and should flow easily and broadly—and International Image Interoperability Framework (IIIF) can be a central element of making that possible.

3 International Image Interoperability Framework

Frustrated by the way in which media collections were growing up within individual collecting institutions that were in turn making individual technology decisions about data stores and presentation applications, technologists at Stanford, The British Library, Cornell, The Bodleian, The National Library for Norway, the Bibliothèque nationale de France (and later, others) set out to design a set of protocols for calling, ordering, and using image files in standardized ways. In 2014, the International Image Interoperability Framework community released the second version of its specifications "intended to provide a shared layer for dynamic interactions with images and the structure of the collections and objects of which they are part. (In June 2015, Artstor joined 10 other institutions in forming the Core Executive Group of the IIIF Consortium.) These APIs are used in production systems to enable cross-institutional integration of content, via mix and match of best of class front end applications and servers." The community set out to create pathways for images to flow through systems from their source, rather than trying to get all repositories and service providers to build everything the same way. Digital image content generated and served up by a range of different image servers could be standardized as output (both the individual image and the structure of an image grouping) for re-use, and could flow, rather than be handed off like plastic water bottles.

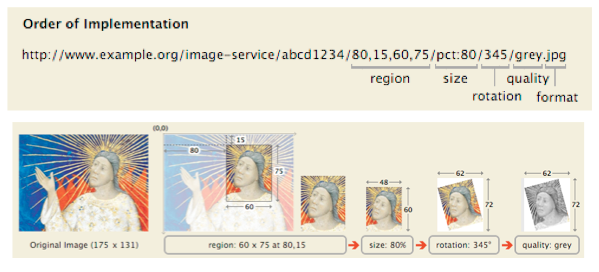

The syntax of an IIIF URL enables the sender or the receiver to request a part, a quality, or an orientation of an image from the source:

IIIF has also established an API standard for the grouping of images, including the sequence and structure of an image set. This defines whether the images are pages of a book or sequence of perspectives on a three-dimensional object as it is turned.

A community of developers and repositories is building out tools to employ the IIIF standards, and content repositories (and their individual image servers) are "plugging in" to the standards. More tools will be needed, and the community's technical priorities are authentication and authorization; search within an object; discovery of IIIF-enabled resources on the open web; and full support for the W3C's Open Annotation community's specification for creating, reading, updating and managing annotations related to image-based resources.

But the standards exist, the benefits of interoperability are very clear, and it is time to put them to use.

4 Path Forward

Artstor's current process in managing images has many positives:

- By creating derivatives and delivering them via a flash viewer, users can access a large file (so as to investigate details) but are not delivered the whole file (enabling us to balance the interest of content providers and rights owners).

- We have built a trusted channel through which collections can be promoted to, and studied by, particular educational audiences in a licensed environment;

- End users of images can (via Shared Shelf) also bring together the 1.9 million Artstor Digital Library images with local image sources (whether they belong to individuals or the institution) in one active image discovery and workspace;

- Content can flow in differentiated way—the Walters' images of works in the public domain in the Artstor Digital Library can, on the Museum's instructions, be discovered openly through the DPLA.

But our process also bears the marks of many work-arounds:

- The dependence upon a given viewer technology inevitably runs into limits (such as the incompatibility of Adobe Flash with iPads).

- The gathering of large image files is burdensome for contributors that struggle with digital asset management and the preparation of files to be released. In doing this work to contribute to the Artstor Digital Library, they are investing in a "one-off" process.

- The scale of Shared Shelf infrastructure required to manage the shared image publishing needs of hundreds of institutions is heavy. On any given day, over 150,000 images (with no restriction on the size of the file) might be uploaded from Shared Shelf to the Artstor workspace or Shared Shelf Commons—and this traffic is continuing to grow. Each transfer requires the generation of derivative files in the format that is read by our image viewer.

- The ability to view assets in the Artstor Digital Library or in Shared Shelf alongside other collections is possible, but clunky—the silo problem noted by the IIIF creators means that users bounce between different viewers and different rules for different collections. In the endless need for primary source material, users continue to have to hunt and peck on an ongoing basis or live with the lowest common denominator (low res JPEGs pulled from various sites or created from books).

Bill Ying, Artstor's long-standing Chief Information Officer, has been an active and engaged member of the working group defining the IIIF approach since its early days, and the community of developers that has led IIIF realizes that traction among image users represents an important step to move the standards from theory to practice and to widespread usage. Given the range of collection rules that Shared Shelf and Artstor manage, Bill has mapped out (and begun to implement) a strategy that should eventually convert all of Artstor's services to an IIIF-based strategy. Doing so begins with the least rights-constrained collections in our network—collections published by Shared Shelf users to the open web (via Shared Shelf Commons), but the strategy can be expanded (as IIIF tools grow).

5 Shared Shelf and Artstor's IIIF map

In this section, we outline the steps that we are taking to implement IIIF in the various services that the Artstor organization provides. This "map" progresses in steps, starting with collections where open access to the content is already the norm—for those collections being managed in the Shared Shelf service and published to open access sites by the institutions that care for the collections. Then, as we advance in our use of the Framework and as the Framework is more fully developed, we plan to proceed toward implementing it for the delivery of other, access-constrained parts of collections that we manage and distribute.

Step 1: Artstor utilizes a particular compression process (FPX format and FSI image server) to convert master files into zoomable images (delivered to users in a Flash viewer, from which users can then download JPEGs for use in presentation). By implementing a system that converts requests between IIIF and the FSI server's proprietary syntax, we have now made Shared Shelf Commons material available via Mirador, a multi-up image viewer built by the IIIF community with the purpose of being able to dynamically and simultaneously render multiple images from multiple repositories for the purposes of viewing, comparing, analysis and annotation."3

Collections, such as Philadelphia Museum of Art Library and Archives, Landscape drawing and American—Exhibitions, can be viewed either in the Shared Shelf Commons discover and use portal (Figure 2, below) or via Mirador (Figure 3, below).

Step 2: Since Shared Shelf cataloging has the capacity to create Work records (i.e. a FRBR style part whole relationship in which data created for the work is then inherited by multiple related display or image records for individual images associated with that work), Shared Shelf users are beginning to experiment with the creation of sequenced works (such as manuscripts) and publishing them to the IIIF driven Mirador viewing environment, where these works can be discovered and used—read, in sequence, or studied as objects. The Mirador reader can call on any open IIIF collections, and hence manuscripts cataloged in Shared Shelf can be published to a space in which they can be studied alongside manuscripts from archives at Cambridge and other IIIF repositories.

Step 3: Harvesting of Shared Shelf collections by the DPLA requires (today) some additional "outside the system" work. As we build an automated "publish to DPLA" function into the system, we will collaborate with DPLA to provide only the metadata (unlike today where DPLA also harvests a 200 pixel preview images) and the IIIF link. In March 2015, Artstor (along with the DPLA, the El Paso Museum of Art, the Museo de Arte de Ponce in Puerto Rico, the Philadelphia Museum of Art, and the Staten Island Museum) was awarded a National Leadership Grant to lower barriers to museum contributions to the DPLA by making Shared Shelf available to museums for contributing to DPLA.

Step 4: As we work out the first level of authorization and access, we can make IIIF links discoverable in in local discovery level systems (like Summons, Primo, or Blacklight). Other local systems will also be able to call upon and read the native images.

Step 5: For institutions seeking to utilize one of the many IIIF-compatible viewers and metadata created or managed in Shared Shelf, we will provide SOLR indexes and IIIF links to be utilized by Spotlight. Spotlight provides a customizable site generation for collections that could highlight a library special collection, a faculty member's own image archive, or even a museum collection. Museums that don't have the technology staff to maintain function-rich collection searching and display could build and brand around the SOLR and IIIF infrastructures without having to invent it all.

Step 6: As we implement the layering of authentication and authorization necessary to manage the subscription access to Artstor Digital Library collections (while allowing Open Artstor Collections such as those provided to the DPLA to be discovered and used by all), our entire image infrastructure will shift. Content will be usable across all platforms (by utilizing HTML5 instead of a proprietary viewer).

Step 7: Creation (by the community or by us) or additional tool extensions (embedding data on download, creation of derivatives, provision of full TIFF image for programs such as our Images for Academic Publishing, image grouping, the encoding of Open Annotation standards and the transport of these annotations with the image asset).

6 Conclusion

Primary source material presents fascinating challenges. A growing community is signing on to using IIIF to helping to bring about networked image content. In addition to the founding institutions, an impressive array of the world's leading cultural heritage institutions are now participating in IIIF—including 9 national libraries; a host of leading US and European research libraries; Artstor, DPLA and Europeana; and a growing number of academic research projects revolving around the delivery and analytics of digital images. The people behind IIIF, recognizing the frustrations of unintentionally locked down collections (even when they're free!) have provided a very clear and realistic path toward exchange and flow (rather than old fashioned logistics). For Shared Shelf and Artstor and the collection-builders and voracious image consumers that we serve, this reduction in the burden of delivery should represent the transition to a new—and networked—stage of content flow.

Notes

1 Since it launched in April 2013, the DPLA has been recognized by the AASL Best Websites for Teaching & Learning, the Nominent Trust 100, and as one of TIME Magazine's 50 Best Websites. Other initial contributors to the DPLA include The Smithsonian Institution, The New York Public Library, The National Archives, HathiTrust and The Biodiversity Heritage Library.

2 Oberoi, S. (2008, April/May). Digital images in museums: Doing the DAM: Digital asset management at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. American Society for Information Science and Technology, vol. 34, no. 4, 17-22. http://doi.org/10.1002/bult.2008.1720340405

3 See a demo of Mirador and more general background and access to the code.

About the Authors

|

William Ying is the Chief Information Officer and Vice President of Technology for Artstor. As CIO, Mr. Ying is responsible for the effective deployment of hardware, databases, and software (both licensed and developed in-house) to maximize the quality of services delivered to the Artstor user community. Prior to joining the Artstor team in 2002, he was the CTO/CIO of Fathom Knowledge Inc from 2000-2002. Established by Columbia University in alliance with 13 partners, Fathom offers lifelong learning and professional development online. Before joining Fathom, Mr. Ying was Vice President of Information Systems at Uproar Inc. Earlier, he held a range of positions in information technology with Chase Manhattan, and the New York Blood Bank, where he developed the first bar code-based Blood Processing Information System, which created a standard for the healthcare industry. He is also an Adjunct Assistant Professor at New York University, School of Continuing and Professional Studies, Art and Humanities program. Mr. Ying received his Doctorate of Engineering Science and Masters of Science from Columbia University and his Bachelor of Science degree in Industrial Engineering and Computer Science from Cornell University. |

|

James Shulman serves as Artstor's President. Working with his colleagues, he developed and implemented plans for creating an organization that now provides a digital library of over 1.9 million images to over 1,600 colleges, universities, schools, and museums around the world; ARTstor also provides the Shared Shelf cataloging and asset management service, and manages a number of free and open services including Images for Academic Publishing and the Built Works Registry (with the Avery Library and the Getty Research Institute). Artstor was among the initial content hubs that supported the efforts of museums and libraries that provided content to the Digital Public Library of America. He received his BA and Ph.D. from Yale and writes and speaks about issues associated with the educational use of images and digital technology, innovative non-profits, and high impact philanthropy. He serves on the board of Smith College and on the Content and Scope working group for the Digital Public Library of America. |

|

|

|

| P R I N T E R - F R I E N D L Y F O R M A T | Return to Article |